What is Emergent Curriculum?

As I type ‘emergent curriculum’ into my phone, it automatically redirects me to ‘emergency curriculum’ – perhaps an amusing topic many teachers might relate to, but not quite what I am looking for this time!

But what about emergent curriculum then?

I first came across this concept in a class at university where I encountered a work sample from the preschools of Reggio Emilia in Northern Italy. In it, the children had embarked on an elaborate visual representation of their city – a group mural – that depicted the town of Reggio Emilia complete with ring roads, power plants, a square (“all cities have squares, so people will know where to go” remarked a 5-year-old working on the project). It all began from the children’s interest in exploring the nature of cities, including what is in them and what makes them work. Later on, I was to discover that all their projects begin not from a teacher initiating the project from a syllabus or a list, but instead from discussion and collaboration with the children themselves.

This is the essence of emergent curriculum. It is derived not from a pre-planned list, but rather, from the interests of the child, things in their physical environment, and events in their daily lives. For many of us, emergent curriculum feels like the opposite of what we might have grown up with, where teachers had a seemingly endless syllabus that we were always rushing to ‘cover’, with little regard for our interests or the curriculum’s relevance to our lives. Emergent curriculum is also distinct from many forms of ‘theme-based’ or ‘project-based’ curriculum, because the projects and topics are not pre-determined, but rather, developed in close collaboration with the children.

Features of Emergent Curriculum

1) Following children’s interests

Rather than begin the week, term or year with a fixed set of topics, a teacher using emergent curriculum might spend time observing and listening to the children to discover where their interests lie.

One of my first projects with the children in my classroom, for instance, began with the snails we kept finding in our outdoor space. I wondered how we could extend this interest, and eventually, purchased a tank for the children to keep them as classroom pets. I engaged the children in conversation about the snails, and they shared their rich thinking and different theories (e.g. Are the snails happier inside or outside the tank? Some thought they were happier inside, free from predators. Others thought they were happier outside, reunited with their families.)

Over time, I placed paper and pens next to the tank, and as their interest grew, they began to draw the snails observationally, noticing things that I would never have picked up on my own, such as the fact that this species had two pairs of horns (one pair to see, one pair to smell!) and that they left a silvery slime trail everywhere they went! This investigation grew out of a natural interest I observed in the children, rather than something I had planned to cover.

Children gather naturally around the tank and share their observations with each other

2) Flexibility: A set of possibilities versus a fixed plan

In implementing emergent curriculum, I do not aim to deliver content or pursue a specific outcome. Rather, I approach planning by generating a series of possibilities and lines of inquiry, knowing that any plans are tentative and will be modified by the children’s response.

With the snails, for instance, there were many potential directions we could have pursued. Would we explore the eating habits of the snails? Their anatomy? The life cycle of snails? The relationship between snails and human beings? Rather than an attachment to one question, we narrowed down the options by testing them out with the children. Their engagement level, the comments made and further insight into their work then provided the indication as to what to pursue next. For example, one 4-year-old hypothesised that snails “don’t like the thunder but they like the rain,” which led us to investigate (at home and at school) whether more snails appeared on rainy rather than sunny mornings.

3) Listening, Observation and Reflection

When implementing emergent curriculum, it is of vital importance that teachers listen and observe children’s work, words and actions and continuously reflect on this during the course of a project. I often record and listen back to some of the conversations I have had with children on a certain topic to get a deeper understanding of what they are thinking and where their interests lie. On a daily basis in our classroom, teachers write a reflection which captures one particularly exciting or engaging interaction from the day. This in turn leads us to potential possibilities for extending the project.

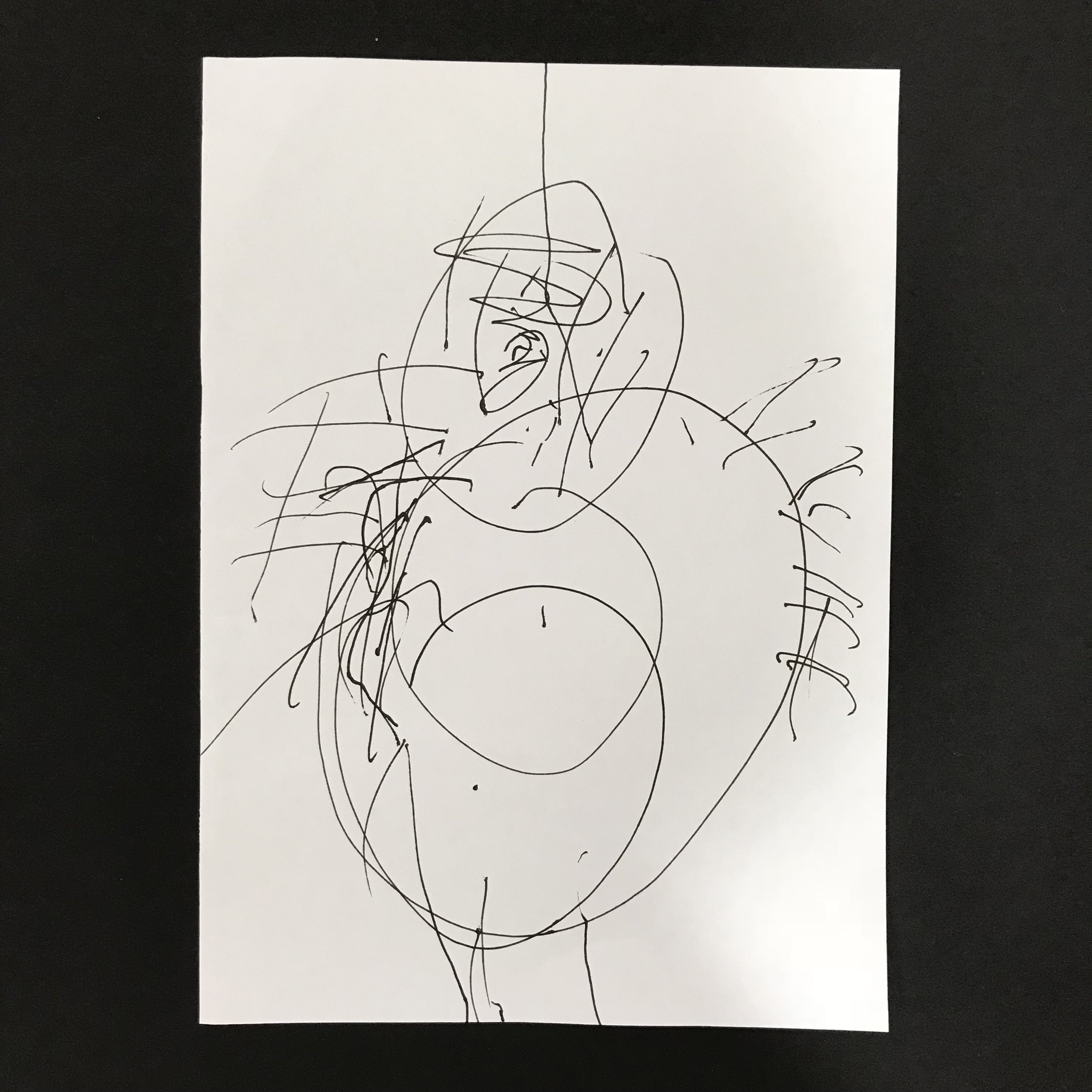

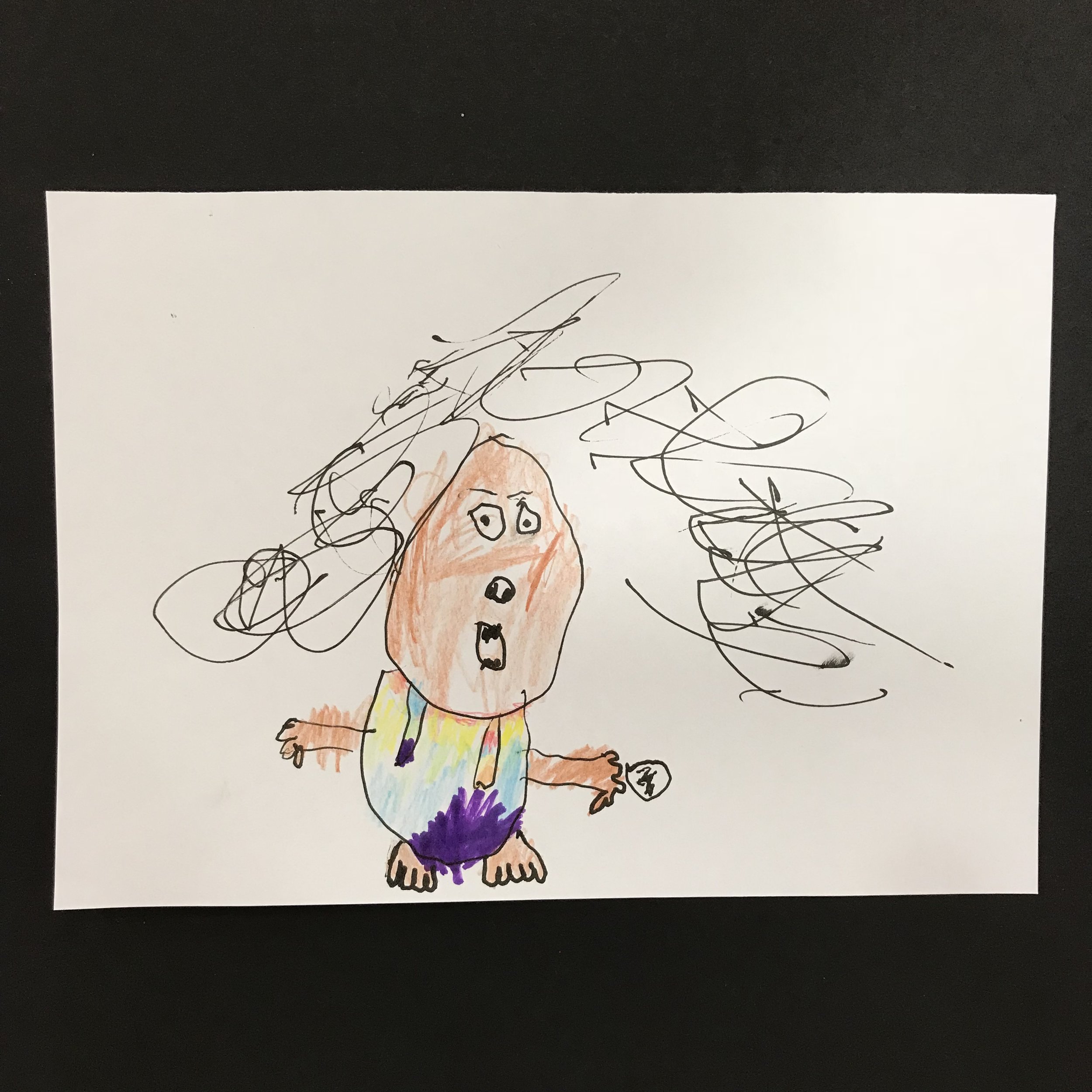

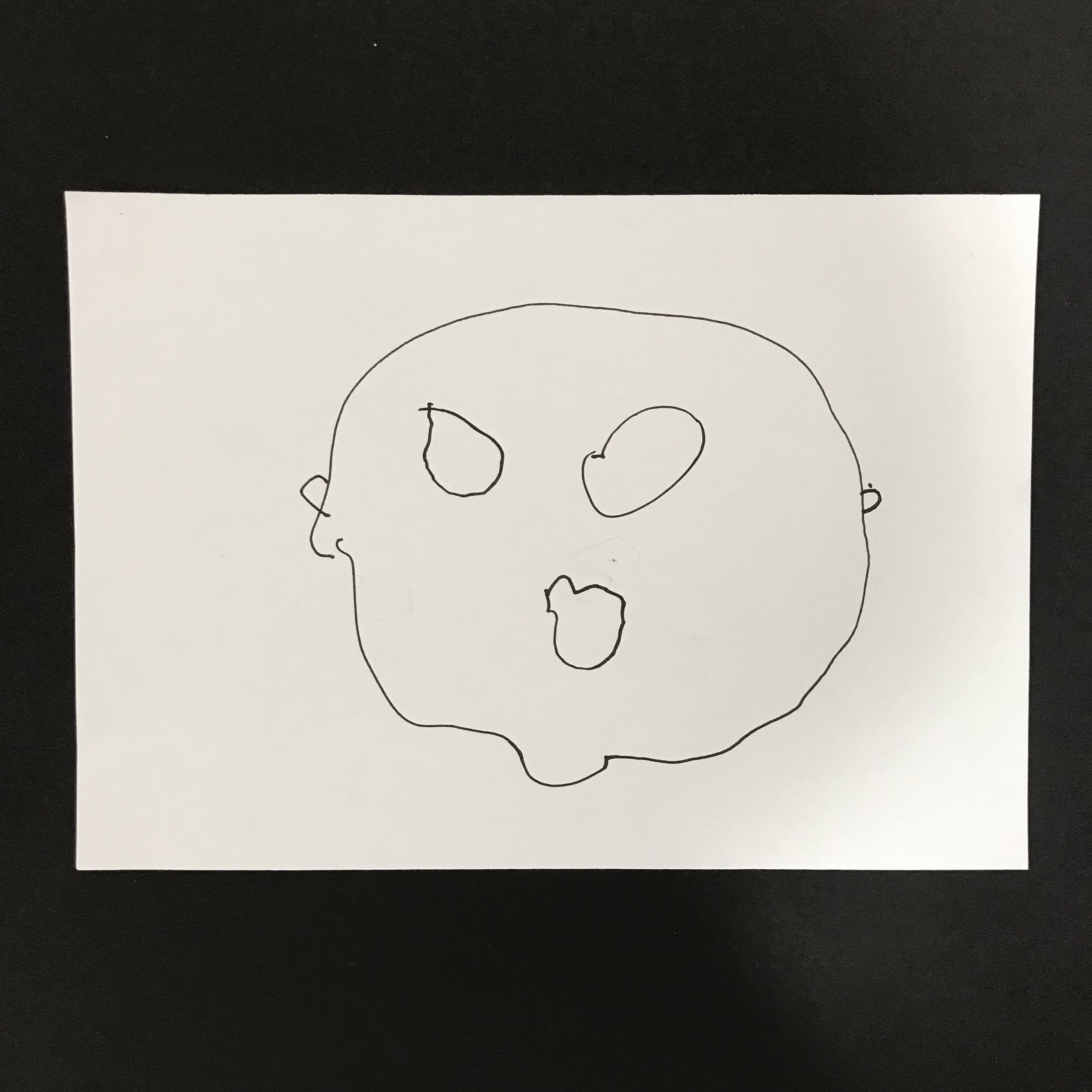

For example, one semester, we observed one child drawing her self-portrait over and over again and were keen to see if others would share this interest. As a next step, we provided the children with opportunities to draw themselves, from photographs as well as with mirrors, which led to a marvellous series of drawings, both of themselves and their friends. Upon further observation, we realised that they preferred to draw from the photographs and began to see that there was a lot more complexity and difficulty involved in drawing from a mirror image. Firstly, with the mirrors, the image was constantly moving since they were drawing themselves, but also they were more interested in watching their own reflections and looking closely at themselves, something adults take for granted but children do not. This led to a new line of exploration involving mirrors and different facial expressions.

What Might this Look Like at Home?

For parents who are keen to incorporate elements of emergent curriculum at home, each of the principles above can inform our approach. The following is an example of what this might look like in practice:

Following children’s interests

If a child is consistently trying to play with the water tap, taking an extremely long time to wash their hands and splashing water around, a parent might choose to follow this interest and set up a series of water play experiences.

Flexibility

In setting up the experiences, rather than commit to and insist on one particular type of activity, a parent could instead consider and even try several possibilities. One experience might involve a tub of water with sponges. Another could be exploring on a rainy day with empty containers. Yet another could be an experience with soap and bubbles in water.

Listening, Observation and Reflection

As the child plays, a parent might observe and identify areas they might deepen and extend the experience. What kind of exploration does the child seem the most drawn to? Does he/she enjoy pouring, splashing, wringing wet items or even the natural movements of water (e.g. “Where does the water from the tap go?”) This attentive but nonintrusive watch on the part of the adult will provide clues for how to go further into the investigation.

Why Emergent Curriculum?

On a personal level, having taught children in both traditional and emergent curriculum settings, I have found it to be an incredible privilege to teach using the emergent curriculum approach. I have been able to observe firsthand how this type of system allows children to become co-creators in their learning, rather than passive recipients of an adult-driven agenda. An agenda which all too often, is one of a curriculum developer writing for thousands of children whom he or she has never met, rather than a specific, unique community.

Emergent curriculum, when used well, can also meet many developmental objectives at the same time, in a way that is meaningful to children. With the snails project for example, children learned to draw observationally, sharpened their scientific observation and reasoning skills, and honed their language ability as they discussed a topic they were passionate about. And as any parent or teacher would know, it is a much more joyful experience to follow a child’s interest than to try to divert his attention away from it!

As you embark on this journey, I am confident that you will be astounded at the capacity of children to direct their own learning and engage in deep, complex thinking. Longer term, this approach will empower them with the kind of confidence and intellectual courage to build productive and meaningful lives for themselves.